Note: This article contains brief discussions about plot points in Milk Inside a Bag of Milk Inside a Bag of Milk, as well as its sequel, Milk Outside a Bag of Milk Outside a Bag of Milk. While I wouldn’t say I get into detailed spoilers, I do talk about some key events including the endings to a certain extent. If you want to go into these games completely blind, I recommend waiting to read this article until after you’ve done so.

Generally speaking, games today try to be smooth, polished experiences. Easing the player in, providing room to learn the ropes and get acquainted with key characters and mechanisms, and avoiding technical hiccups are all important features in making games as enjoyable as possible to the widest audience. Certainly, I’ve been known to rain praise upon games that do these things well and criticism on those that don’t, because whether they succeed or fail, the fact of the matter is that most games are trying to do these things. This makes it all the more jarring when a game seems diametrically opposed to such ideas, not out of incompetence or inexperience, but out of a deliberate desire to make something off-putting. That’s the story with Milk Inside a Bag of Milk Inside a Bag of Milk (henceforth referred to as Milk Inside) and why it’s fascinated me to such an extent since playing it.

Milk Inside wastes no time shoving you into its twisted, surreal world. Like some other visual novels, it features full narration, however here it’s done not by professional voice actors, but by a rudimentary text-to-speech system. This is not one of the newfangled “AI voices” that are all the rage nowadays (which is perhaps good given the horrid ethical implications of them); this is your classic Microsoft Hazel voiceover, where every syllable receives the same emphasis and complex writing often breaks it altogether. For instance, when Milk Inside writes out “W h a t?”, which is clearly meant to be an elongated “What?” Hazel narrates it as “W” “h” “a” “t”, simply saying the name of each letter in turn. It’s almost comical listening to it struggle through more involved lines, and it undercuts the tension in more than one scene. But it got me asking the question: why have this lacklustre narration when none could possibly be more tonally effective?

This extends to the story, which meanders around its core plot point of a girl going to the store to buy some milk with some truly strange inclusions. There’s an extended discussion about taking an uneven number of steps when one foot is on concrete and the other on grass. Regular fourth-wall breaks happen, with the girl both addressing the dialogue options you select (which seem to represent the voice in her head) and the player directly. One exchange in the store features a looping pair of dialogues that goes on for so long I thought the game was actually broken the first time I played through. If you make improper choices, you’ll be kicked back to the start of the game; there’s no save system in place, so you just have to play all the way through again.

None of these feel “right” to go through, and while some do contribute to Milk Inside’s underlying themes of mental instability, social anxiety, and trauma, they make it come across as abrasive and unwelcoming, almost hostile to the player. What seems like it will be a simple trip to the store with some sprinklings of horror and discussions of mental health instead becomes an often deeply philosophical experience that left me debating between labeling it pretentious nonsense or too highbrow for me. I still struggle to come up with what exactly the game is trying to say with its many deviances: is it an examination of the way trauma and anxiety can ostracize one from the world? A meditation on the nature of games and the way their stories are told? Something else that hasn’t crossed my mind? Maybe all of the above?

Then there’s the art, which can best be described as a pixel miasma. In monochromatic shades of pinkish-red, each scene Milk Inside presents you with is so lacking in detail that most become utterly meaningless when unmoored from context. Even in the midst of the game, half the time you can’t tell what you’re looking at. Scenes are compressed and blown out into a pixelated hellscape to the point where a section of the game asking you what you see in a particular image feels like cruel mockery more than anything, daring you to see something in its mangled abyss. The figures you talk to at a few points in the game almost blend into the background, their forms too alien to fully comprehend. It’s a wholly ineffective means of communicating the detail of each scene, forcing you to rely on instinct and assumption to glean any meaning, which nonetheless feels rather apropos given the unstable nature of the protagonist’s psyche.

All these creative decisions combine to make Milk Inside a surreal and unpleasant game to play through, and one that I would struggle to recommend to anyone. Yet there’s something about it that’s compelling nevertheless. It’s an extremely brief experience, lasting less than half an hour to see all the endings, but that digestibility is offset by just how strange everything about it is. It’s a half hour game that spawned more than an hour of ruminating on my part, from debating the thematic implications of janky text-to-speech to staring at a riot of pixels wondering if there’s actually some hidden meaning I missed. And despite the fact that its tone is all over the place and I never really felt immersed in its world, I still left Milk Inside feeling unsettled, to the point where turning off the lights and plunging my room into darkness brought on a sense of creeping dread and ghoulish imagery. But what makes this truly fascinating is that Milk Inside is only half the story.

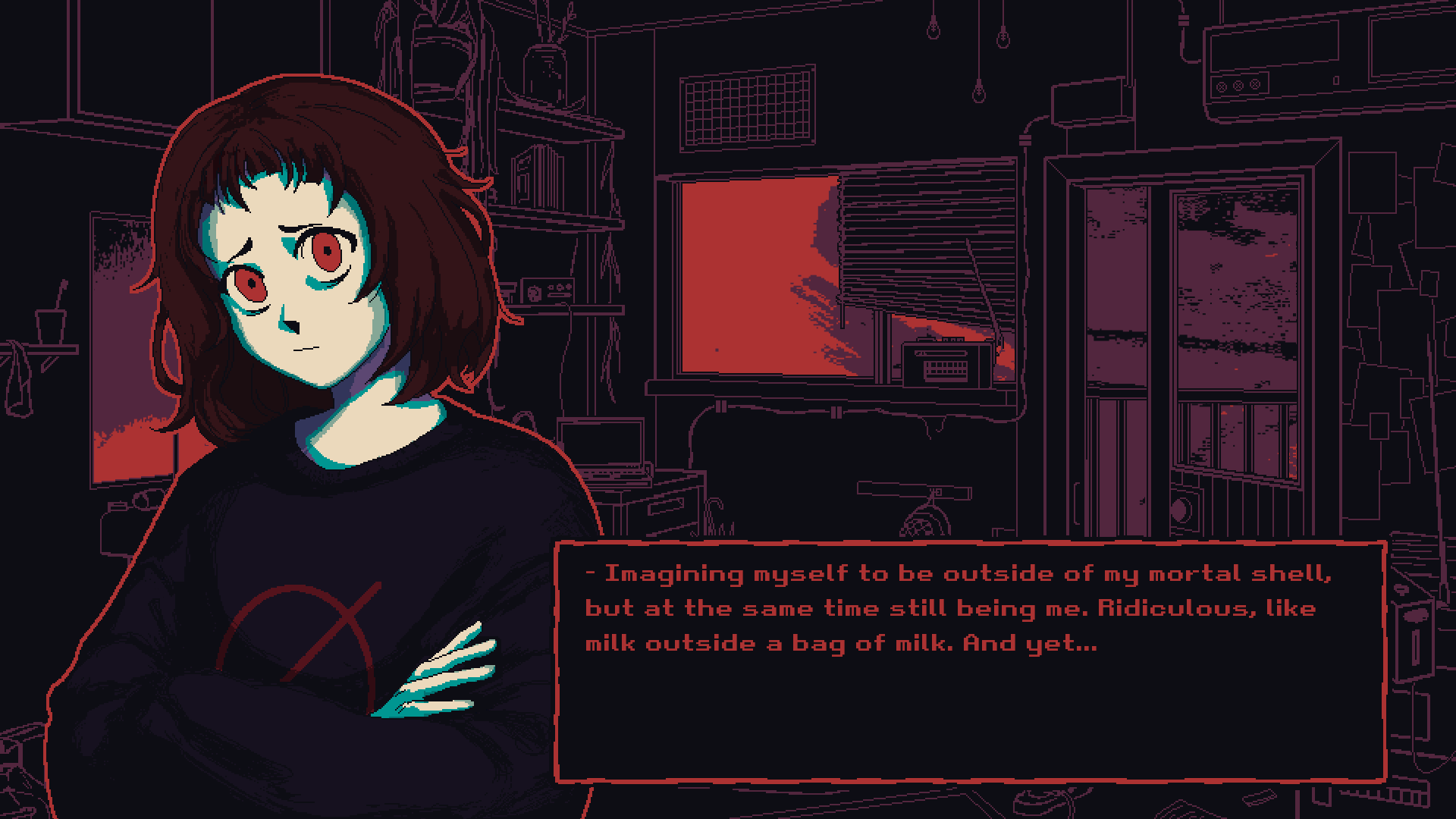

In stark contrast to Milk Inside’s distorted, monochromatic minimalism, Milk Outside a Bag of Milk Outside a Bag of Milk (from now on abbreviated to Milk Outside) feels almost luxurious, featuring fully-animated cutscenes bookending the playthrough, detailed character sprite artwork, and a fleshed-out soundtrack. It’s a decidedly more “high-budget” approach to what remains an incredibly esoteric experience, but I’m torn as to whether it’s actually more effective. Certainly, Milk Inside can feel a bit goofy and amateurish at times, but that meant its emotional impact on me was all the more impressive. Milk Outside is clearly going for that, and succeeds, but it makes Milk Inside’s “accidental horror” feel like an even greater feat.

From a thematic perspective, Milk Outside carries forward a lot of what was set out in Milk Inside, but here there are aspects that are more explicit. For instance, we see that the protagonist is on a host of medications for her condition, and she struggles with the side effects of taking them versus not. She becomes paranoid that there’s a corpse behind the door leading into the kitchen, but then is clearly shown her fears are unfounded. Depending on the choices you make, it’s possible to get a more concrete idea of the protagonist’s past and what led her to be in the state she’s currently in. However, there’s still surreal sections that are open to interpretation. A monster confronts her outside her bedroom, demanding that she vow to never drink milk and injecting her with some sort of venom. Each of the game’s five endings are more confusing than the one before, going from a recounting of Milk Inside’s events from a different perspective (including a wholly unnecessary use of an ableist slur that wasn’t even present in the original game) all the way to lengthy philosophical conversations with a pizza restaurant.

This broadened scope makes Milk Outside a much more involved game than Milk Inside, but it comes at the cost of a lot of rough edges being smoothed out. There’s an actual save game option now, and the text-to-speech voice is gone, replaced with gibberish voiceover reminiscent of Animal Crossing. Background imagery is more easily parsable, which is necessary to facilitate a point-and-click style section midway through that’s also the source of most of the game’s path branching. Those different paths take more work to find too; I actually needed a guide to figure out how to get all the achievements for Milk Outside, whereas Milk Inside was much more straightforward. There’s more going on, but the result is that individual moments are less memorable. After completing Milk Inside, there were so many parts that stuck in my mind due to how strange or confusing they were, but in comparison I struggle to recall any details about Milk Outside’s different endings beyond the basic premises.

None of this is to say that Milk Outside is a bad game by any stretch. From as objective of a perspective as I can muster, it’s technically a better game, featuring more content, better graphics, and more consistent storytelling. But this is why subjective evaluation of games is so important; in becoming a more broadly appealing experience, Milk Outside strips away many of the oddities that made Milk Inside so thought-provoking. Perhaps the limitations of Milk Inside were simply due to time and budget constraints, but even then, the fact that such quirky decisions were made as cost-saving measures still speaks to a desire to provide a particular experience, surreal and off-putting as it may be. I didn’t enjoy playing through Milk Inside, at least not in the traditional sense, but that felt like the point; the game deliberately creates a discomforting, unwelcoming atmosphere that makes you just as lost and alienated as its protagonist. It feels like bad game design, but in this case, what’s bad is also what’s best.