Developer: Studio Élan

Publisher: Studio Élan, Circle Line Games

Played on: PC

Release Date: June 16, 2025

Played with: Mouse

Paid: $0 (Key provided for review)

Warning: This review contains brief discussions and descriptions of self-harm and related topics. While I don’t go into extensive detail, reader discretion is nonetheless advised.

It’s always challenging to go into a piece of media with preconceived notions. As a reviewer, I strive to approach each game I cover on its own merits, yet I admit it’s next to impossible to go into something truly blind. By the time I’ve looked at enough press material to determine whether or not it seems like a good fit, I’ve inevitably built up some idea in my head of what the experience will be. Plus, the very fact that I’ve determined something appears to be up my alley already means I’m going in with at least a hope – if not an expectation – that it’s something I’ll enjoy. Of course, this doesn’t preclude me from coming down hard when things don’t pan out the way I thought they might or heaping praise when they do, but at the bare minimum, it regularly puts a fear in me that I’m ill-equipped to fairly evaluate whatever game I might be looking at.

This concern became even thornier when I was sent a code for A Tithe in Blood; the latest in Studio Élan’s line of yuri (i.e. lesbian) visual novels. I won’t mince words: Highway Blossoms (Studio Élan’s first game in this line, at least according to Steam) is my favourite game of all time. It’s a wonderfully heartfelt love story between two women that’s perfect in how imperfect it is. It isn’t an idyllic romance where girl meets girl and everything’s peaches and cream, nor does it play into worn-out genre tropes as a means of cheaply stirring up conflict. Its characters feel grounded, despite their occasionally outsized personalities, and it thoroughly earns every plot beat it sets up and subsequently pays off. It’s a game that broke my heart and put it back together, one which prompted me to write an entire essay that I’ll probably never publish due to how painfully personal it is, and despite it being a completely linear narrative experience without any player choice, I nonetheless find myself being called back time and again.

So how on Earth could I possibly give a fair judgement on A Tithe in Blood, given that context? The answer may very well be that I can’t. And hell, I’m already late to the coverage party, thanks to the overwhelming stresses of moving putting me on hiatus for over a month. Yet this is an important review for me. It’s been a while since a piece of media affected me the way A Tithe in Blood did, even longer if we’re strictly considering video games. For better or worse, it’s a game that I have Thoughts™ about, and I want the opportunity to share them, even if it’s just on my lonely blog in the ever-growing digital expanse. If you think I’m too biased one way or another, feel free to click away, but I encourage you to stick around; there’s something special here, and it’s more than worthy of discussion.

A Tithe in Blood is a supernatural romance visual novel that revolves around Honoka Asakawa — a young, disaffected woman in university who’s harbouring a dark secret: she is a regular practitioner of blood magic. Living in modern-day Sapporo, Honoka spends her days attending classes and mostly drifting through life, but at night she uses her powers to travel back in time … well, kind of. Technically, she does arrive in her home city in the Meiji era, however it’s a “bubble reality” of sorts: carved out of the regular flow of time, its inhabitants are isolated, carrying out their lives in an unchanging space. Centred in this world is Yasue: a mage from the era who is also the reason for its current predicament. While details are scant at the outset, it’s eventually revealed that Yasue was targeted by an opposing mage, who cast a spell to sequester her reality away as a form of eternal torture. Prior to the events of the game, Honoka’s use of blood magic ended up dropping her into Yasue’s world, at which point the kind-hearted mage supported and befriended her. With little connecting her to the present day, Honoka regularly visits Yasue, fostering the one relationship in her life that feels genuine in spite of the risk to herself.

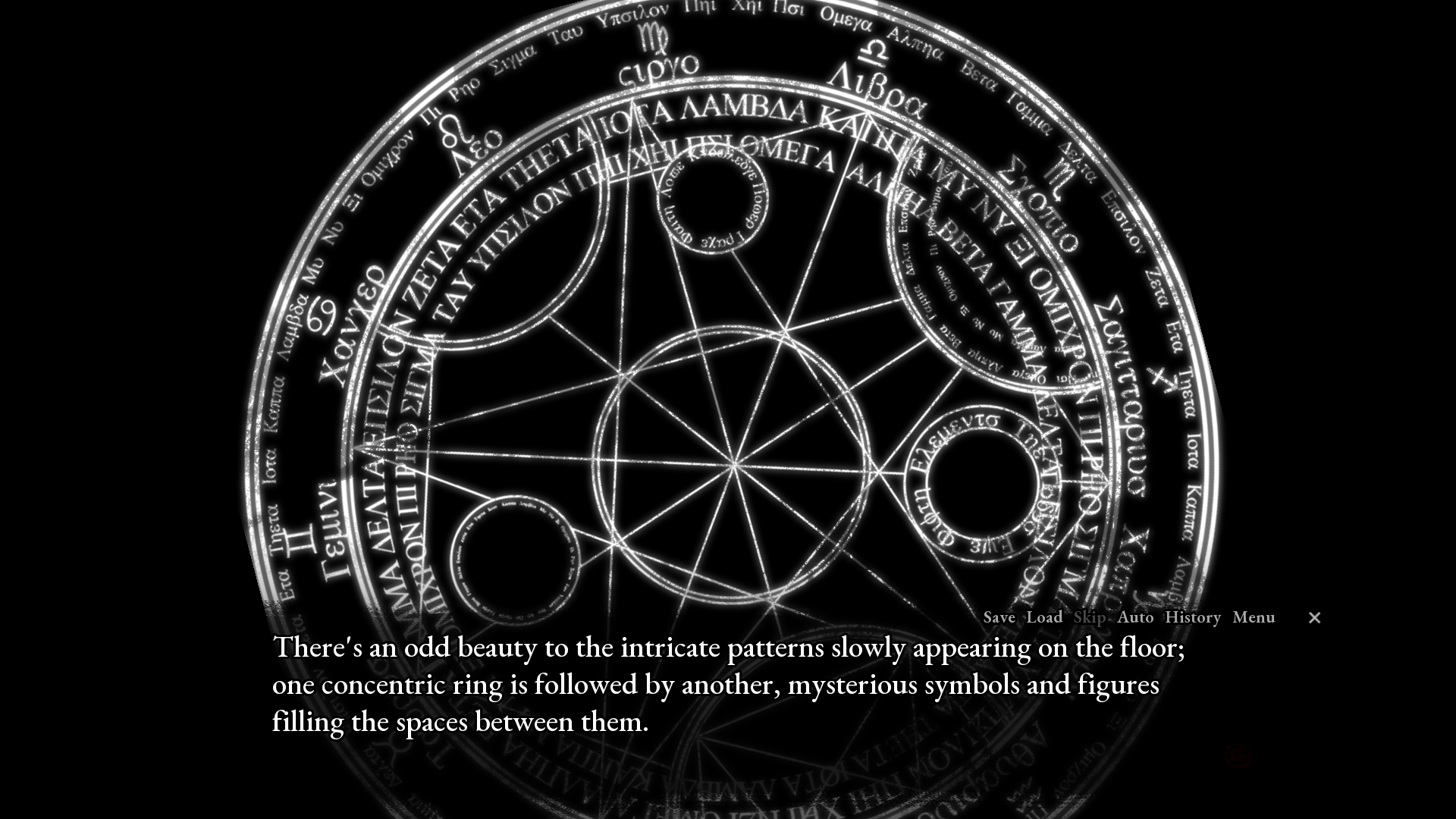

Unlike regular magic, which requires one to be birthed from a line of mages, blood magic is a long-lost art that can be practiced by mere mortals, however it comes at a far greater physical cost. Where mages are able to perform conjurations and manipulations simply by focusing their minds, blood mages must make use of meticulously-drawn sigils and, of course, a blood sacrifice. For Honoka, this takes the form of slitting her wrist, allowing the blood to trickle down to the floor and activate the ritual. A Tithe in Blood does not take this lightly, either. Each time you launch the game, a much-appreciated content warning appears, and it’s well-warranted. Despite the fact that it’s being done for the purposes of a magic spell, the descriptions and images of Honoka’s self-harm can be extremely triggering. This is only amplified as the story progresses and Honoka spirals deeper into depression and self-loathing. While the physical descriptions get briefer, the weight of the actions become even more consequential, trapping Honoka in a cycle where scarring herself further and attempting to push past her body’s physical limits feel like the only relief from the crushing pain of her life.

I think that A Tithe in Blood handles the challenging topic of Honoka’s mental health extremely well, neither glossing over it to avoid its harsh realities, nor fixating on it to the point of becoming misery porn. As someone with no shortage of history with her own mental health, I found many of Honoka’s struggles to be deeply poignant and relatable, despite our surrounding circumstances being different. At the time A Tithe in Blood takes place, Honoka has recently lost her parents, and the grief and memories hang over her, threatening to swallow her whole. As she puts it at one point: “Everyone else’s life kept on going, when mine stopped.”

While my parents are thankfully both still alive, I nonetheless know all too well the feelings of alienation and disconnection Honoka describes. All sorts of factors can cause a hole to open up inside one’s self, and watching the world continue to turn without you can be maddening and debilitating, at best. Maintaining healthy relationships is challenging at the best of times, and when something has suddenly uprooted your life, it can be nearly impossible. I think it’s why Honoka is so drawn towards Yasue: for one thing, her visits and Yasue’s effortless compassion distract her from past trauma and make her feel loved and appreciated in a world that otherwise feels like it’s abandoned her. However, the stories of the two characters also parallel one another: both had their realities ripped away from them involuntarily and are simply struggling to get by in the new world they find themselves in.

As Honoka and Yasue increasingly gravitate towards each other, they begin to open up, though Honoka in particular still attempts to keep certain aspects of her life at arm’s length. We learn that Yasue harbours strong resentment towards the mage who locked her away, in stark contrast to her generally pleasant, light-hearted demeanour. Meanwhile, early on in the game, Honoka admits the truth of her magic to Yasue, who is understandably disturbed by the fact that Honoka is literally harming herself to see her. Despite this, Yasue seems to take it in stride, accepting that if it’s a price Honoka’s willing to pay and she’s not endangering herself, she’s in no position to stop her.

I’ll admit, there is a part of me that wonders if this is love-inflicted selfishness on Yasue’s part, but I can also appreciate that — as the only point of light in Honoka’s increasingly dark world — there would be a certain anxiety associated with shutting her out for her own safety. It’s an area where the relationship between text and subtext in A Tithe in Blood gets a bit muddy: while I don’t read it this way, I could certainly see a less charitable interpretation suggesting that the game advocates for self-harm if it gets you the relief you need from a bad situation, however temporary. Whether it’s willfully ignorant on my part or not, I instead choose to understand it as the classic trope of sacrificing things for love, with the problems only truly starting to arise once Honoka lets the balance shift to where her own life no longer matters. And to the story’s credit, it shows Yasue becoming increasingly distressed as Honoka pushes herself further and further; it’s not as though she simply glosses over the toll it’s clearly taking on the woman she loves. Additionally, it’s not like Honoka is content with the way things are: she pours herself into magic research in the hopes of finding a way to break Yasue free from her cage and bring her to the present day, allowing the two to be together without Honoka continually having to pay her dreadful tithe.

This devotion to Yasue’s world (perhaps in part because its relatively fixed nature means it comes with far less baggage) means that Honoka is a sort of transient in her own reality. I brought it up briefly before, but a central theme of A Tithe in Blood is how overwhelming passion can be warped into an all-consuming obsession that devours everything else in one’s life. Honoka doesn’t maintain friendships aside from Yasue, and is disconnected from the world around her, outside of sporadic checks online to keep up with news and the like. In the midst of her struggles, she states, “The world keeps changing, but I can’t keep up. Frozen in time, I can only watch as others live their lives so effortlessly.” It’s a soberingly relatable comment, particularly as someone who regularly feels out of step in everything from interpersonal relationships to career growth.

In A Tithe in Blood, there are inklings that this may begin to change when a bubbly librarian named Shino enters Honoka’s life, warmly accepting her as she is and lightly encouraging her to break out of her shell. However, as is so often the case with real-world mental health struggles, there’s rarely, if ever, a miracle cure, and Honoka’s staunch refusal to truly open up to anyone in her life leads to her continuing to spiral into despair behind the scenes. It’s painful to watch, especially since I’ve both been there myself and seen others I care about fall into it as well.

This is all to say that, on the balance, A Tithe in Blood is not a happy story. It’s a tale of grief, loss, and futility, perceived or otherwise, and if you’re looking for something comedic or uplifting, I recommend you look elsewhere. That’s not to say it’s a wholly negative experience, however: on the contrary, the presentation of the narrative is of a consistently high quality so as to make it an incredibly compelling read, in spite of its dour themes. Characters are distinctive and well-rendered, and the relatively infrequent “set piece” images are beautiful, adding to each scene they depict. The music complements the story beats well, and while the voice acting is only available in Japanese (and therefore I don’t have the cultural context to fully speak to its quality), I nonetheless found it immersive, with each voice feeling appropriate for its respective character. As for the writing, there are a few points where tense inconsistencies and repeated word use give an occasionally amateurish tone, but these are thankfully infrequent enough to only be a minor quibble.

It’s challenging to discuss things too much further without delving into spoiler territory, but there are some more general points around the way the story progresses that warrant discussion. In act two of the game’s four acts (plus an epilogue), the perspective shifts away from Honoka and begins retelling the narrative from another character’s point of view. In the process, it rapidly becomes clear that Honoka has been unknowingly drawn into the middle of some sort of conspiracy. It’s a troubling development thematically, as suddenly certain faces that seemed welcoming and sincere in act one reveal a duplicitous, possibly sinister nature, making Honoka’s fears about not belonging in the world and it being against her seem distressingly realistic.

To be clear, this isn’t playing into the trope of “the conspiracy nutjob ended up being right the whole time”, but it did make Honoka’s situation feel hopeless, as I found myself becoming increasingly paranoid that nobody actually had her best interests at heart. It also doesn’t help that — as the acts progress — the true intentions of these two-faced characters remain somewhat obfuscated, which made me question each action they took, even when they claimed it was all for the greater good of keeping Honoka safe. Lastly, while there is a bit of a redemption arc for at least some of the characters in question, I still struggle to accept their betrayal of Honoka being outweighed by their positive impacts later on. I suppose this could just be down to me projecting my own insecurities onto A Tithe in Blood, but I can’t deny that there came a point where I had to briefly disconnect from the game and acknowledge the fact that it had clearly forgiven individuals I was still harbouring a grudge against. It wasn’t that the story didn’t convince me that Honoka had made her peace with them, either; it was simply that I struggled to convince myself that she should have.

This all brings me to the climactic moments and denouement of A Tithe in Blood, which are incredibly powerful and well-executed, even though they didn’t quite hit me the way I expected them to. After the emotional gut-punches of Highway Blossoms, I was waiting for similar moments here, but they never quite came. Part of this is down to the ultimate villain, whose callous, calculating acts replaced my feelings of sorrow and subsequent relief with anxiety, anger, and despair. Perhaps a larger issue is that — much like Honoka herself — the more human elements of the tale weaved by A Tithe in Blood are periodically dwarfed by the supernatural aspects, favouring spectacle and high stakes over subtlety and relatability.

This culminated in the final experience being no less of an emotional rollercoaster compared to its predecessor, but the physical effects it manifested were markedly different. This isn’t a game that brought me to tears, but one that deftly plucked at my heartstrings, particularly with its profoundly empathetic portrayal of Honoka. It made me sympathize deeply with her plight and want desperately for her to be safe and succeed, to the point where — as the story hit its crescendo — I was left tense and vibrating, taking shuddering, shallow breaths while praying everything would somehow work out. It truly feels like more of a personal drama with light yuri elements than what I would consider a “traditional” yuri romance novel; specifically, there’s a notable absence of many of the “cute couple” moments and carefree lovey-dovey-ness I typically expect from the genre.

I really can’t fault A Tithe in Blood for that, though. Given the serious nature of much of its subject matter, I think it would be challenging, if not impossible, to seamlessly weave those elements in without completely upending the tone and making it feel like it was trivializing the very real themes of depression and grief. I more so bring it up to further cement the idea that if you’re going into it off the back of games like Highway Blossoms, you may be surprised to find how substantially different it can feel.

That being said, looking at Studio Élan’s back catalog, this isn’t the first time they’ve delved into dark themes in their games, and I think it shows here. A Tithe in Blood is not without its faults, but a lack of compassion for the difficult struggles its characters face is certainly not one of them. It unflinchingly depicts the pain that can be caused by trauma, especially when one lacks a good support network, and manages to inadvertently tap into hardships and insecurities I’ve dealt with personally without feeling tokenistic or patronizing. I do take umbrage with how quickly it attempts to flip the morality of certain individuals, and the scope of the narrative occasionally loses itself in grandiosity. However, it’s still an exceptionally well-told story, and one that kept me glued to my screen from start to finish. At the top of this review, I talked about struggling to approach A Tithe in Blood due to my preconceived notions and expectations surrounding it. To close it, I’ll say that — while sometimes such ideas can damage one’s ability to properly appreciate a work — it’s a sign of truly beautiful art when they’re instead shattered altogether.

9/10