Developer: Studio Élan

Publisher: Studio Élan

Played on: PC

Release Date: September 30, 2025

Played with: Mouse

Paid: $0 (Key provided for review by Studio Élan)

I have a bit of a history with magical girl media. Growing up, whether it was due to gender expectations or just a lack of interest, I wasn’t particularly drawn to shows like Sailor Moon, though I do recall watching occasional episodes of Cardcaptor Sakura when they came on TV. In high school, though, a friend introduced me to Puella Magi Madoka Magica (Madoka Magica for short), and everything changed. Seeing a magical girl story that delved into mature subject matter (along with having stunning animation and music) was like a cosmic shift in how I perceived a genre that I had once written off as “just those silly shows about girls in frilly outfits”. I showed it to my girlfriend at the time. Hell, I showed it to my dad. I got low-key obsessed with it for a while, and even now it stands as one of my favourite anime of all time.

Madoka Magica also became something of a genre touchstone more broadly, to the point where — when Lock & Key: A Magical Girl Mystery opened by assuring me that its magical girls fight the forces of darkness purely by choice and with no lying or misrepresentation by the higher power calling them to it — I couldn’t help but smile at what seemed to be a deliberate nod to one of its big reveals. It also had me wondering how Lock & Key would differentiate itself from the contemporaries it seemed familiar with, especially considering that I went in with effectively no prior knowledge beyond the fact that it was another game by Studio Élan, meaning lesbians were (thankfully) inevitable.

The short version is that, as the full title suggests, Lock & Key: A Magical Girl Mystery plays out much more closely to a traditional whodunnit story for a good chunk of its runtime, focusing more on characters talking and investigating for clues rather than getting in grandiose magical battles. However, the prologue nonetheless sets the scene with a generation-spanning conflict between the forces of Benevolence and Malice, with the former calling upon young women to fight to defend the world from the latter’s army of corrupted humans known as Consumed. It also establishes Lock & Key‘s main twist on the magical girl formula: each girl receives their own special transformation and abilities that will aid them in their fight against the Consumed, but once they turn thirty, they lose their magical form and powers.

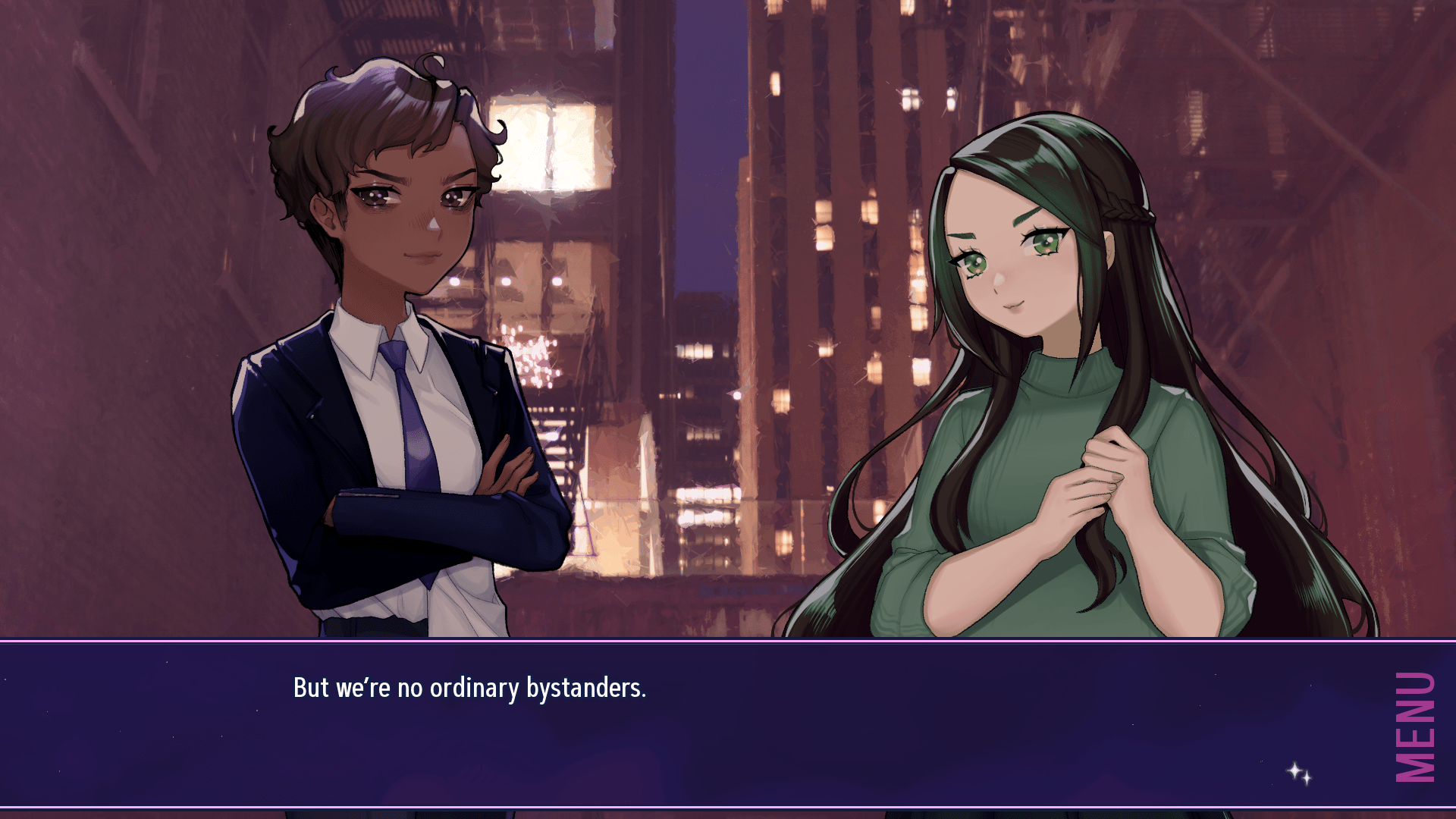

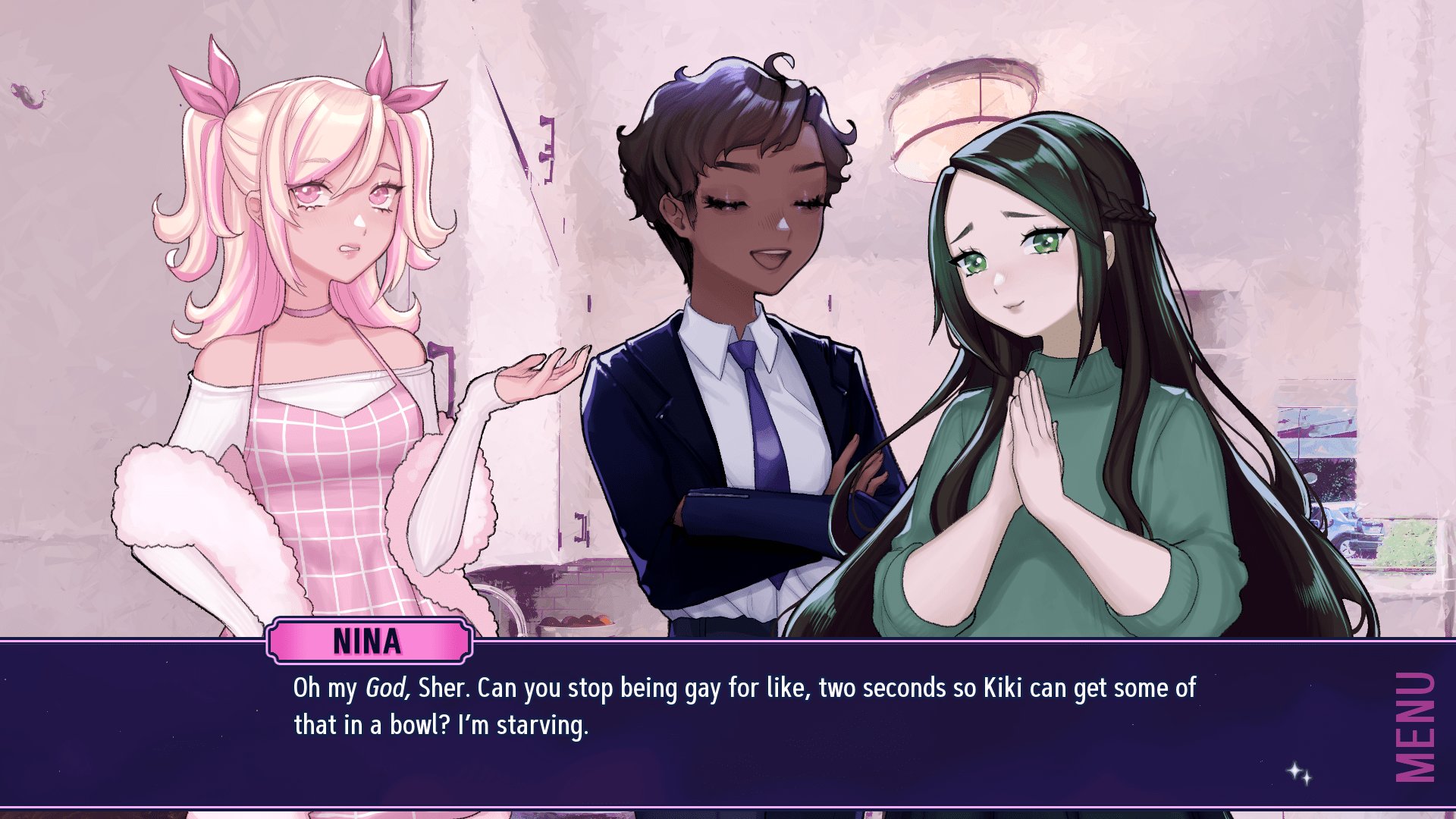

That doesn’t stop some from calling it quits early. In its opening moments, Lock & Key introduces Kealey and Sherri Cohen: a happily married couple in their late twenties who retired from being magical girls after high school, but still utilize their powers (while they’ve got them) to aid in their day-to-day work. For Kealey, this takes the form of using her shapeshifting ability to be the greatest cat burglar in all of Chicago, robbing from the ultra-wealthy and giving to … well, her and Sherri, mostly. As for Sherri, she’s a private investigator who’s (rightfully) sick and tired of the cops bungling things up and trampling all over her cases in the name of making themselves look good. Her powers of clairvoyance enable her to look back in time and see the path that inanimate objects took in the past 48 hours, so long as she can make physical contact with her target. A great asset in solving crimes, to be sure, but a bit difficult to use with those not in the know around; since the existence of magical girls is kept a secret from the world at large, to the cops it looks like she’s just messing with the placement of evidence. This hasn’t stopped Sherri from being decently successful as a PI, though, thanks in part to her perpetually annoyed, foul-mouthed “friend” Natasha periodically letting her into crime scenes after the cops leave.

The case of The Locked Room Killer is the mystery that Lock & Key‘s plot pivots around: a long running investigation into a serial murderer who somehow manages to commit each crime inside the victim’s home, all without showing any signs of forced entry or exit. The trail seems to be running cold until Nina — the Cohens’ bubbly former magical girl colleague turned pop star — suggests sneaking Kealey into a crime scene to use her aura reading powers. Upon doing so, Kealey quickly detects the telltale signs of a Consumed, but also something … more. So begins a race against time to figure out who — or what — could be perpetrating the killings and put a stop to them once and for all.

As if that weren’t enough to worry about, while leaving the crime scene, the Cohens stumble upon a young magical girl by the name of Ruby (or Nightshade when she’s working) struggling in a fight against a powerful Consumed. Upon rescuing her, the couple learns that Ruby’s only been on the magical girl beat for a week and a half and clearly still lacks a lot of the necessary skills. At Ruby’s request, the two agree (a bit reluctantly, in Sherri’s case) to provide some light training to set her up for success. Unbeknownst to Ruby, a tragedy in the Cohens’ past is influencing their relationship with her; not in any sort of malevolent way, mind you, but it does mean the Cohens know more than they let on.

These disparate plot threads gradually weave together as Lock & Key progresses over its roughly six to seven hour runtime, culminating in an ending that can be significantly influenced by the ways in which the characters react to various events in the game. In contrast to the other Studio Élan visual novels I’ve played, Lock & Key provides several opportunities for player choice to come into the equation, leading to divergent paths in the narrative. It’s worth noting that these branches are fairly rudimentary and mostly just affect the ending, though. This is not a game like Mice Tea where a single choice can immediately send you down an entirely different plot thread unlike anything else in the game; rather, each decision here will — at most — have a handful of unique lines of text in the moment. Otherwise, the cumulative impact of the calls you make seems to just be stored in the background, with each one tipping one of two scales in one of two directions. Once it’s time for the grand finale, the heavier side of each scale determines which of the four endings you get. To be fair, that could be me oversimplifying the dynamics at play; there’s certainly room for, say, some choices to outright lock you out of a particular ending. Whether or not that’s the case, the fact of the matter is that if you pursue additional endings after seeing one, you’ll find that the game’s optional skip function that automatically fast-forwards through previously-read text will make 95% of the game a blur. It feels like it was designed for one playthrough, with the additional outcomes added to give a bit of custom flair to each person’s experience, rather than being the driving reason to play the game.

Of course, that means what matters more here is the depth of the narrative on offer, rather than the breadth, and I have to say that while Lock & Key‘s writing exudes the polish I’ve come to expect from Studio Élan’s offerings (barring a few minor typos), in practice it doesn’t always land. The biggest culprit here is the way in which the game shifts narrators. This is something that Studio Élan has done before (most recently in A Tithe in Blood), but here it happens far more frequently, and it harms the flow of the experience. At various points in the game, the story is told from either Sherri, Kealey, or Ruby’s perspective, and this usually changes from scene to scene. This is fine on the face of it, but Sherri and Kealey’s internal monologues are written in a very similar voice, and the text boxes for said monologues don’t specify who they’re coming from. This meant there were countless times where I started a new scene, incorrectly assumed who the narrator was, read through a bunch of the story, eventually realized my mistake, and had to rewind and re-read everything that had happened so far to make sure I was properly in the know about who was thinking what.

This wasn’t the only time things got confusing, either. There’s one point in the story where a character unleashes a massive wave of energy, and then in the next scene a different character mentions sensing an intense aura. Seems reasonable to assume they’re talking about the one that was just shown, right? Wrong! The latter scene actually occurs two weeks later, and the detected aura is related to a completely separate entity that shows up with next to no forewarning. The way the game is written makes it seem like this was foreshadowed, but as near as I could tell, it wasn’t. Granted, I played through Lock & Key a bit sporadically, so there is a possibility that I just forgot this critical detail. However, even if that is the case, the juxtaposition of the two scenes makes it harder than it needs to be to keep track of who created what aura and when.

I’m also not sure how I feel about the characterization of the game’s antagonist. Initially, the reveal caught me off-guard and had me completely hooked, excited to learn more about their motivations and schemes. As things progressed, though, things started to get a lot more muddled. Multiple scenes played out with them basically showing up somewhere, teasing that they wanted to reveal the details of their plan to the other characters, and deciding instead to peace out. Not only did it make the narrative feel padded out, but it took their character from being confident and menacing to instead coming across as confused and juvenile. They had some great scenes, don’t get me wrong, but also several where I found myself asking, “What even was the point of that?”

To cap off the issues, I really don’t like how Lock & Key does its stereotypical “big romantic scene right before the climax” bit. Sometimes those can work depending on how their handled; for instance, if there’s some plot reason why the leads have to wait until the next day to take on the big bad, that night is a perfect opportunity for some nerve-calming romance. Unfortunately, in Lock & Key‘s case, it opts to have the two characters in question stop to share loving sentiments and a moonlit kiss … all while someone they care about is in imminent mortal danger. This is not even a “we need to rest up to make sure we’re in tip-top shape to rescue our friend” situation; this is “we’re literally mere steps away from the antagonist’s lair, but let’s stop and gaze longingly into each others’ eyes for a spell”. And to top it all off, apparently their intimate moment makes them completely forget their plan, as after establishing earlier that they were going to try to sneak around and get the drop on the villain, the next scene sees them eschewing stealth entirely and strolling through the front door to meet their foe face-to-face.

I know this has been a lot of complaining on my part, and it probably seems like I hate Lock & Key, but the reason I’m so passionate about my issues with the game is because when it hits, it does so with aplomb. Its mysteries intrigued and kept me guessing as the pieces gradually fell into place. On my first playthrough, many decisions felt like they could be deeply consequential, leading to me taking my time thinking about them before going with my heart. And I cared about how those choices would play out, because I cared about the characters! It’s a testament to Studio Élan’s writing that everyone (with the deliberate exception of Natasha) is so immediately likeable and charming pretty much from the get-go; after only one session playing the game, I already found myself animatedly chatting to a friend about how I was low-key crushing on Sherri, Kealey, and Nina!

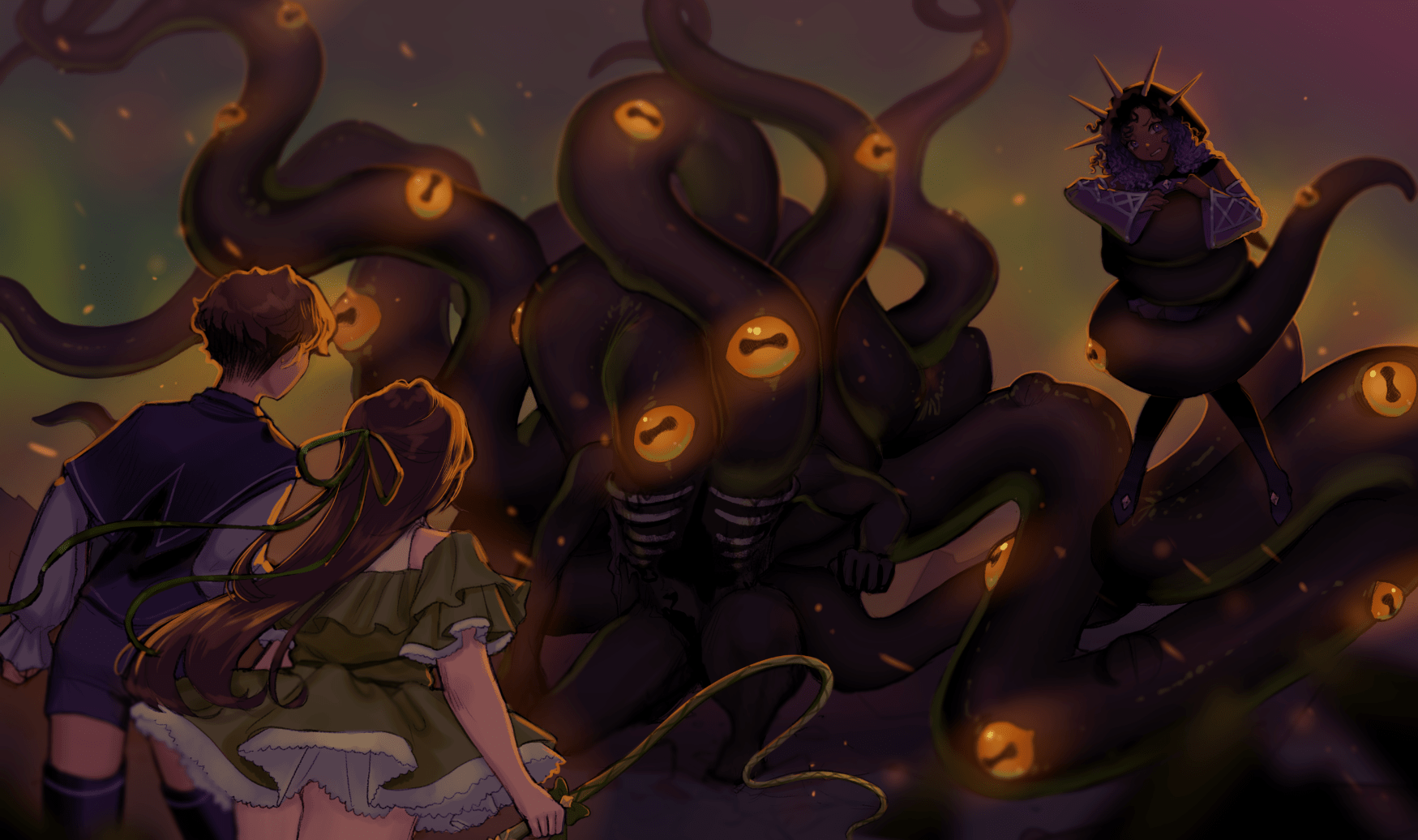

I also appreciate a lot of the extra effort that’s put into living up to the visual part of the visual novel genre. While Lock & Key isn’t as full of unique setpiece images as some games of its ilk, it frequently utilizes camera movements on the ones it does have to give a sense of action to the proceedings. The early scene where the Cohens rescue Ruby is of particular note here: the single art piece is zoomed in on, panned over, and has special effects overlaid on top to simulate various actions taken in the battle, and it works well to bring the player into the action. This extends to the character sprites as well, with certain scenes having them zip around the screen to simulate everything from hyperactivity to badass combat moves. Sure, it’s just taking static images and sliding them around the screen, but it nonetheless manages to be pleasing and entertaining when it could easily be corny or annoying. The only real issue is that sometimes the artwork isn’t high enough resolution to support the tight zooms all that well (even on my regular HD monitor there was a fair amount of pixelation), but what it lacks in detail is made up in dynamism.

It’s also worth touching on some of the themes and subject matter in Lock & Key. While nowhere near as emotionally taxing as A Tithe in Blood (though it does get surprisingly dark and gory at times), it delves into some discussion points that I really want to explore further. For one, considering I recently turned thirty myself, the game’s themes of growing up and losing out on the things you could do in your youth hit me extra hard. It’s a strange milestone to hit, simultaneously feeling deeply consequential and also completely irrelevant, and the uncertainty and apprehension various characters in Lock & Key face around it manage to feel relatable despite the magical overtones. Even something as simple as the occasional off-handed comments by Ruby about people in their late twenties being considered old made me give some extra consideration to myself and my place in the world. She clearly doesn’t mean anything by it, and I’m sure that’s true for most young people, but it really puts things into perspective.

To get a bit personal, I recently looked through my dad’s old record collection with him. There were bands and albums I recognized, and some I didn’t, yet it was all music I would unequivocally consider “not of my time”. Most (if not all) of it holds up today, I’m sure, but the thought of listening to it feels a little like reading a history book; fascinating and valuable, but lacking the immediacy of something that came out in my lifetime.

And now I have my own record collection, featuring several albums I remember listening to in high school and post-secondary, and many more that have come out in the last five or so years. It’s contemporary and hip and full of classics and … I can’t help but wonder if in another thirty years I’ll be going through it with my nephews, with them having the same thoughts I’m having now. All these feelings have come up for me while playing and contemplating Lock & Key, and I certainly don’t begrudge it that. Aging is strange and difficult and confounding, and while it’s not always pleasant to think about, the way Lock & Key explores it through the lenses of its various cast members is nevertheless captivating and cathartic.

I also truly appreciate the extra bits of diversity that are interspersed throughout the story. A simple example is how an old group photo shows Sherri wearing shorts and having unshaved legs: while it isn’t commented on or explicitly pointed out by the game (and arguably doing so would lessen its impact), the fact that it’s there does an admirable job of normalizing different preferences around hair removal for women. As someone who can frequently get rather meticulous about hair removal, I welcome having more media promoting the idea that it’s completely fine to let things grow out a bit; it certainly doesn’t make you any less of a woman.

There are also times where diversity is brought to the forefront and incorporated into the plot’s more emotional beats, such as the reveal of one magical girl being a trans woman. Now, I’ll admit, I’m predisposed to be invested in any sort of trans femme representation in media, however I like to think I’d appreciate this narrative beat even if I wasn’t. What makes it great isn’t just that it’s handled very matter-of-factly (i.e. there isn’t a contrived scene where the character has to come out to someone — and the audience by extension), but that it naturally feeds into the themes I discussed earlier around growing up. In essence, Lock & Key discusses both the “cosmic validity” of trans people (that is to say, being accepted and validated by the universe, even if individual people in day-to-day life don’t offer the same respect), and the complex emotions that can arise when there’s any semblance of that validation being taken away: in this case, aging out of being a magical girl. You want to believe in the fact that nothing can change who you are deep down, but when you’re forced to lose something that was at minimum helping to keep the intrusive thoughts at bay (and often doing much more), it can feel like an attack on your very self. I read it as an allegory for the distressing trend of trans rights and healthcare being rolled back in countless places around the globe, and while it doesn’t change the fact that fighting to protect these rights is something everyone should be involved in, I will always appreciate Lock & Key‘s emphatic refrain: you are valid, no matter what.

So this all leaves me with some rather complicated thoughts on Lock & Key: A Magical Girl Mystery. As far as word count is concerned, I’ve spent roughly equal amounts of time here griping and praising, but obviously that’s not any kind of real metric to arriving at a final rating. Hell, now that I think about it, I haven’t even mentioned the soundtrack: regular Studio Élan collaborator Sarah Mancuso returns to compose a score that — if I didn’t know any better — I’d think was ripped straight out of a popular anime, incorporating angelic vocals into action themes to give them the uplifting and ethereal sound I’ve come to expect from genre classics. There’s an entire “Data” screen in the pause menu that includes brief bios on each of the different characters and a few in-game locations and events, which is invaluable for catching up and refreshing yourself on things if you’ve had to take a bit of break. Overall, it’s clear that a lot of time and passion went into crafting Lock & Key, even if it doesn’t always hang together as well as I might have hoped. Maybe that’s bumping up my score a bit higher than it otherwise would be, but I also can’t deny that I enjoyed my time with it, in spite of my complaints. I wouldn’t exactly call it light and breezy, but it might actually be the most accessible Studio Élan game I’ve played. It’s a solid entry point to their writing and world-building; it’s just a shame that — ironically — it’s not quite as magical as some of their other offerings.

7.5/10